I reach into the back of the hallway closet and rest my hands on a threadbare kimono that my father will never wear again. Once its blue fabric enveloped his plump shoulders, and its long collar exposed a strip of flesh running from his sternum to his navel. My dad’s entire torso, save that sliver of skin, is stained with swirls of ink.

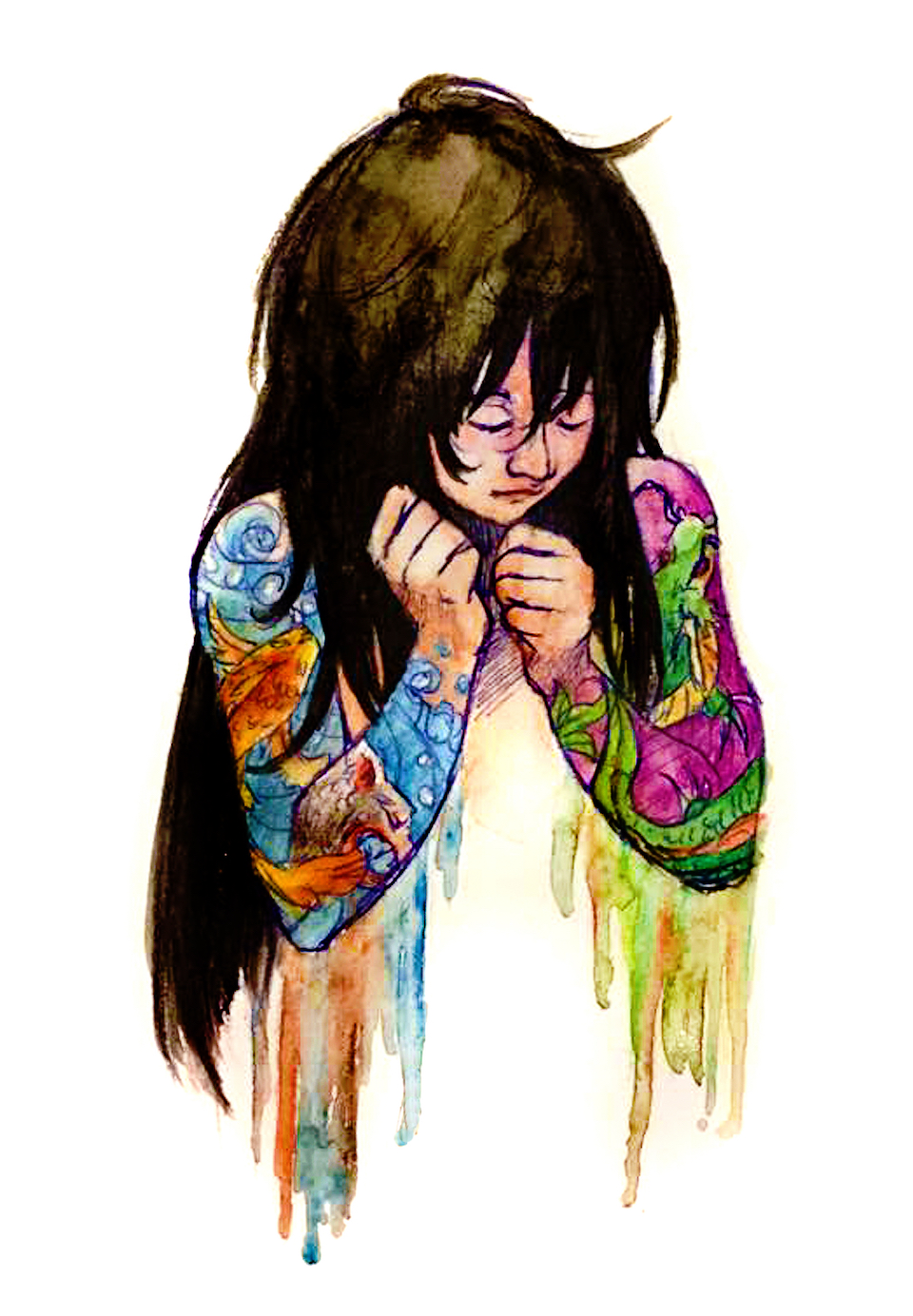

Mirrored dragons adorn my father’s chest. Red koi fish thrash around his arms as if fighting against a current. Cherry blossom tattoos tumble down his back, and a fanged snake curls up his spine. Every square inch of ink on my dad’s body is a threat. Tebori tattoos are carved into their bearer’s skin with small spears and take hundreds of hours to complete. My dad endured days of pain just to decorate his body; inflicting suffering upon others came to him naturally.

I run the kimono’s ultramarine fabric between my fingers. It hid my father’s tattoos the way the sea’s inky surface conceals man-eating creatures. My dad last wore it for an impromptu parent teacher interview ten years ago. I start to feel tightness in my throat, and I dig my nails into the kimono. What the hell am I feeling guilty about?

So what if I haven’t talked to my dad in months? I can only remember him acting like a real father once in my life. Back when I was seven years old and still lived in Japan, the kids in my class bullied me constantly. They would steal my lunchbox and dump its contents around the schoolyard. Each day, I jumped up and down with my hands over my eyes and hollered until my face reddened. Once I was so hungry, I picked grains of rice off the ground and chewed on them, trying to ignore the grains of sand that crunched between my teeth. My teacher would always watch me wail after recess. Sometimes he’d even wince at me, thinking I deserved to be bullied. He had heard rumours that my dad was a former Yakuza.

I’d walk home after school with my stomach as empty as my lunchbox. It kept happening until my older brother Sho found me curled up and crying up in my bedroom. Sho wrapped an arm around me. He made me tell him about the bullies and relayed the story to my father.

My dad threw on his kimono and sped to my school, his teeth clenched the entire ride. He stormed into my teacher’s office, dragging me behind him, his voice thundering like hailstones plummeting onto a tin roof. He pointed at the exposed unmarked strip of skin on his chest and shouted he was not a Yakuza. He claimed he didn’t have any tattoos and kept his three-fingered hand tucked in his pocket.

My father told my teacher that he was living honestly. It was true at that time; my dad was working as a waiter and he wasn’t getting paid much. But my teacher had heard too many rumours of my father’s past. He demanded my dad show him the hand he was trying to hide.

My dad hesitated, but his face quickly turned purple. He yanked his hand out of his pocket and brandished it like a weapon. “Fine!” He screamed “I shouldn’t deny what I was, and if I ever go back to that, it’ll be because of people like you. You won’t let me be anything else!” My dad puffed out his chest, pulled back his collar and flashed the tattoo over his heart. “And you said it yourself — I’ll always be a Yakuza. So you’ll be dealing with a Yakuza if I ever see my daughter cry again.”

Not only did the bullies stop picking on me, but my grades also suddenly improved.

For Halloween that year I dressed up as my hero. I grabbed my magic markers and drew soaring dragons, roaring tigers, and rabid wolves all over my arms. When my mother saw my attempt at Tebori, her voice was shrill. She hauled me into the shower, screaming that Yakuza were criminals and killers. I crossed my arms as water melted my tattoos away and told my mother she was wrong about the Yakuza because my daddy was one of them. She immediately drove the back of her hand into my face, knocking me right off the bath stool. I stared up at my mother with my palm pressed to my tingling cheek.

She towered over me, her forehead as ribbed as a washboard. She had never hit me before, but her eyes showed no remorse. She struggled to keep her voice steady, and said she could never love my dad if he really was a Yakuza.

Not too long after that, my dad started working for his old boss again and my mom divorced him. My father will forever be a criminal — he has that written into his skin.

Tap! Tap!

I reach into the hallway closet and shove the kimono back where it belongs: out of sight. I then stride to the front door. When my father phoned this morning to say he’d be coming over to my apartment for dinner, I felt a rush of blood to my head and nearly told him to get lost. But I thought of him coming back from work to his empty house every single night and never seeing a warm meal waiting for him.

My father scratches his forehead as he enters the hallway, and a couple of greasy strands of hair straggle down his forehead. When we lived in Japan, his nickname was “Loan Shark,” but “Panda” would be a more suitable name for him now. His big belly spills out from beneath his chest and his dark eyes sink into his pale face.

“You alright? You look exhausted.”

My father nods and pushes his stringy black hair back over his pasty bald spot. “Where’s the food?”

I saunter over to the stove and set a bowl of soup onto the kitchen table. I had cooked enough for three people, but Sho refused to sit at the table when he came home. I figured that was for the best anyways — he and my dad would just be at each other’s throats if they were to eat together.

“Have as much as you want, I’m not hungry,” I say. My father smacks a tea cup onto the table and wipes his mouth with his sleeve.

“You need to come here more often.“

“I’m busy with work.”

“That’s no excuse. You can’t only decide to be my father when you have nothing better to do.”

“I made sacrifices for you and your brother.”

“We only got bullied because of you!” My heart starts racing. “Everyone at school knew you were Yakuza, but they wouldn’t dare touch you, so they came after your kids.”

“How can we accept you? You just keep blaming others!” My teacup slips out of my hand, spills onto the table. “I’ve had enough.” I turn and walk into the hallway.

My dad grabs me from behind and pushes me up against the closet door. “Don’t talk to me like that. I’m not the child here.”

“Let go!” I shout and try to break free of my father’s grip. “Get off of me!”

I hear a door swing open as my brother comes racing down the hallway. He charges into my dad and the hallway closet crashes open. The closet rack comes tumbling down and all the clothes wind up on the ground.

“No! Get off of him!” I grab hold of Sho’s shoulders and try to pull him off my father, but he’s far too heavy. Sho shouts as he pins my dad to the ground and holds a fist right above his face. “He always wants to use force to get his way. Why’d you let this jerk come into our home?”

“He’s our father!”

“No, he’s not. That’s what he pretends to be. He needs to leave.”

“He can’t go yet.” I clench both my fists. “I need to settle things with him.”

My brother glares into my dad’s eyes, but eventually lowers his fist and climbs off of our father. “If I hear you yell again, Mai… I’m kicking him out of here.”

My dad used to beat Sho when he was a teenager, but my brother got stronger as he grew older and started hitting back. If Sho didn’t move out of the house and get an apartment with me, I think he might have killed my dad.

My father ignores the blood dribbling out of his nose and stares at the kimono that has fallen out of the closet along with all the other clothes. He snatches it off the ground then hobbles over to the kitchen table. He manages to cradle a soup bowl in his right hand although it has no index or ring finger. When I was young, my father told me that a fish had bitten off the two fingers. He claimed that the creature had been merciful. The fish had supposedly spared the middle finger because he understood that my father desperately relied on it to flip people off.

“The Fish” turned out to be the nickname of my dad’s Oyabun. When I was eight years old, I learned that Yakuza members were obligated to slice off a finger joint as an apology for failure. People were terrified of my father because of his missing fingers. In fact, the Japanese public is so afraid of the Yakuza that the children’s show Bob the Builder was nearly banned in Japan. Bob only has 4 fingers on each hand, and the government was afraid that this would make children believe he was a gangster.

My dad glances at me and then takes a long look at the kimono. “I can’t believe you kept my old waiter uniform after all these years.”

“Of course I did… I looked up to you so much back then. Why the hell did you have to go back to being a gangster?”

“I’m a playboy not a busboy. I couldn’t spend my life emptying ashtrays and refilling teapots. That was the only work I could find in Japan when I quit the Yakuza.”

“But you don’t live there anymore. People here aren’t terrified of your missing fingers and tattoos.” I wipe my eyes with the back of my hands. “Why are you still involved with the Yakuza? I know you still send money back to your Oyabun.”

“You deserve a father, but I can’t pretend to be one.” My father pulls on his old work uniform. The Tebori tattoos on his arms disappear under the kimono’s sleeves.

He heads for the door and I know I may not see him again for months. I think back to the first time I can remember seeing him. When I was four years old, I told my mother there was a strange man sleeping in our house, and she laughed. She said the man was my father and he had always lived with us. He would leave for work each day before I woke up and only come back after I went to bed. Every night after I first saw him, I tried to stay up as long as I could, hoping I’d finally meet my daddy. But I never seemed to be able to fight off sleep and it carried me off into dreams.

I didn’t learn of the terrible things my father did until I got older. My drunken dad once crippled a man in a casino by slamming his head into a slot machine. He also owned a love hotel linked to human trafficking rings, and would hunt down debtors like wounded animals. My daddy would demand endless payments, and some of his victims ended up taking their own lives.

I take a deep breath as I watch my dad leave my apartment clad in his old work kimono. I remember being a child, sitting and shivering in the shower as my makeshift tattoos disappeared. I now dream about the wild creatures inked into my father’s skin being washed away.