In 2011, Htay Tint was living as the CEO of a restaurant chain in Toronto, observing with anticipation as his home country, Myanmar (Burma) began to open up to the outside world after nearly five decades of isolation under military rule. This year on November 8, the country hosted historic elections in which the people of Myanmar voted overwhelmingly for the National League for Democracy, the non-military opposition party led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The outcome of this election, and how the military will respond to it, will play an influential role in determining the country’s future.

Notable reforms leading up to this point have included developments in the areas of education, press freedom, labour organization, Internet access, and the release of political prisoners. With the election now complete, Myanmar will face questions about the effectiveness of these reforms, and the challenge of establishing a new government.

Perhaps most significantly, recent reforms have exposed unresolved questions about Burmese identity; democratization efforts continue to be undermined by conflict and an ongoing civil war in many parts of the country. Battling a history of factiousness, the central challenge for the new government will be to foster an environment of free and fair political interaction.

Now a mature student, studying Myanmar from afar, at the University of Toronto’s Asian Institute, for Tint the turbulent history and the uncertain future of the troubled country are particularly close to heart.

Life in Mandalay

Tint was born in 1967 in Mandalay, Myanmar, where his father was posted as part of his military service. He came from relatively upper-class circumstances, spending his childhood in Kyak Kyi, which is part of Myanmar’s Pegu Division. His maternal grandfather was a prominent landowner, and his family ran a land administration business. Tint’s family also ran a general store and a transportation business called “A Way Phay Cars” which provided long distance travel services from Pegu to cities such as Yangon, Mawlamain, Mandalay, and Taunggi to assist with agrarian and forestry trades. Undisrupted, he could have expected a comfortable upbringing.

Around 1970, however, Tint’s life was completely upset. The region where he lived came under the control of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), the most powerful militant group in the area at the time. The CPB required Tint’s family to redistribute their lands, for which they received minimal compensation. His aunt then went underground to join the CPB, and he has not seen her since.

Punctuated by the reality of civil war between armed ethnic groups such as the Karen National Liberation Army, armed rebellion groups such as the CPB, and the Burmese military, Tint’s childhood was governed by fear. He regularly witnessed his peers drop out of school to work for their families, friends and relatives were arrested for suspected connection to rebellion movements, and teachers arrested and sentenced to manual labour to work as porters in service of the Burmese army.

After being accused of supporting rebellions, Tint also recalls being arrested and beaten as a teenager in high school. Especially disturbing for him, however, is the memory of how the military would storm the town when mounting an attack against the rebels.

“We [would] hide in our homes, nearby temples and rivers…military troop[s] decided to take all women, so women with their children [were] arrested by…our own military, own government he recalled.

Tint described how frequent fighting would cause students to run from their classrooms in search of refuge. Those who were arrested and made to work as military porters, had less than a 50 per cent chance of returning home and being reunited with their loved ones.

Resisting the regime

It was in 1988 that Tint, by then a trusted student leader in his town, called together a conference to decide how to stand against the Burmese military government. After establishing a strike committee of farmers, workers, academics, and students and being elected General Secretary, Tint was sent to attend a general meeting at Pegu with other representatives, and declared that his hometown would join and support the general strike against the Burmese regime.

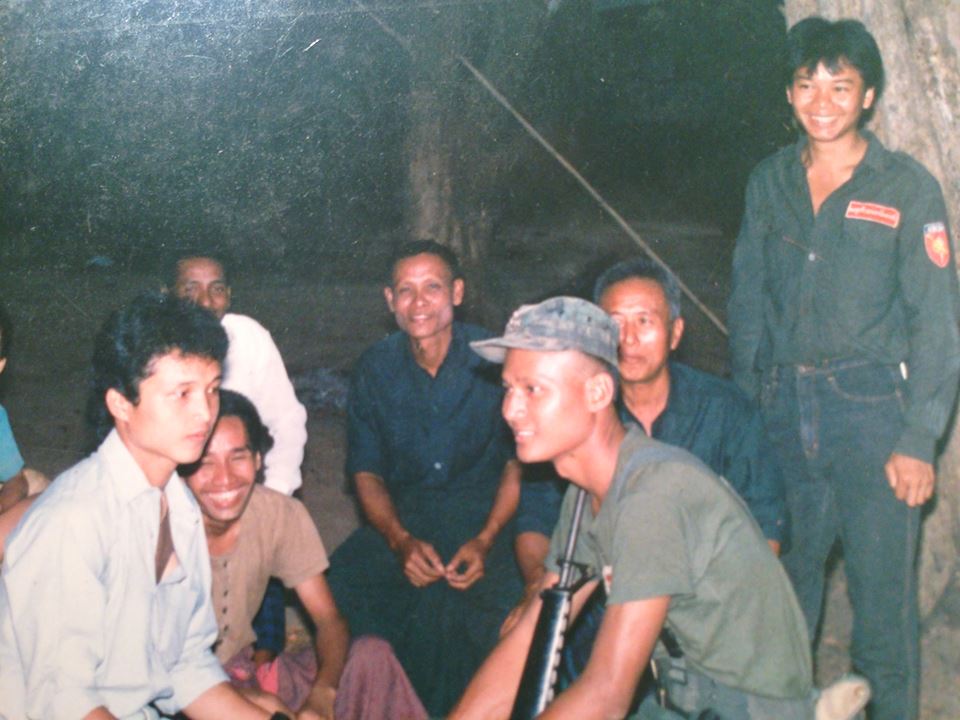

From this decision came the founding of a students’ army to fight against the military government in 1988. The group was known as the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF).

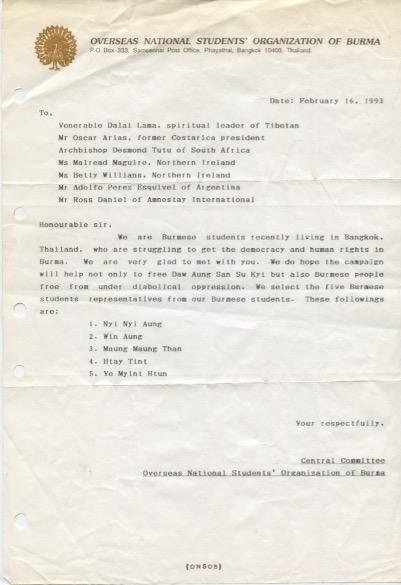

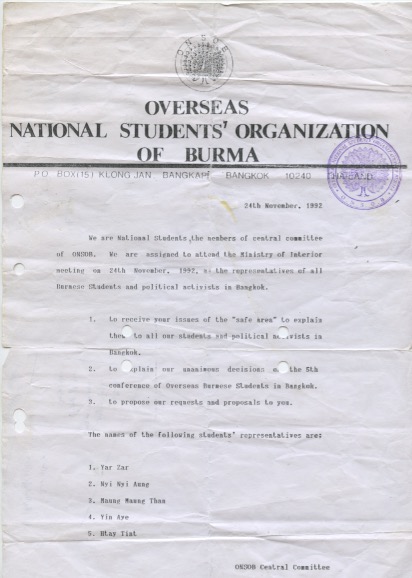

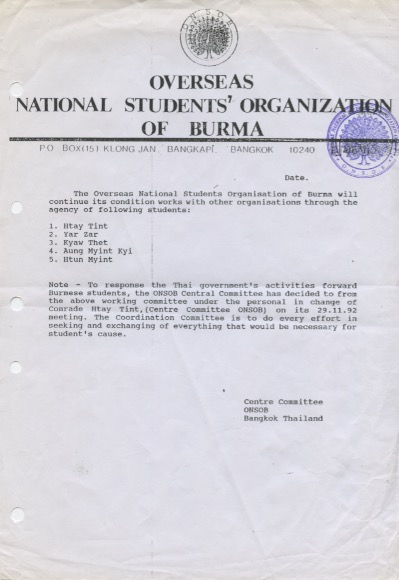

In 1992 he was sent as a representative of ABSDF to attend a student conference in Bangkok, Thailand, for the Overseas National Students Organization of Burma (ONSOB). At the conference, Tint was nominated and elected as a central executive committee member of ONSOB. The group elected to use non-violent opposition instead of armed resistance against the military government.

In Thailand illegally, and wanted by both the Thai and Burmese governments, Tint and his fellow students were arrested when protesting the Thai government’s proposal regarding the country’s ‘Constructive Engagement Policies’ towards Burma at the ASEAN Conference.

This moment was a turning point in Tint’s life — the one that brought him to Canada.

“When we were arrested includ[ing] some female students… they put all of us together in same room. One night, a group of police [came] into the inside and [tried] to take some female students without any reason… [M]e and another [two] students leaders, Ko Shein Myint, a teacher from Rangoon, and Khun Shwe Thike, a student leader from Taunggi, stood in front of [the] female students … faced [the] police and [told] them we can not let it happen at the middle of the night. They hit us and all other student[s] close to them. [T]hey realized that they were inside of the room with too many of students, and they [ran] back.”

“And soon, they arrived back with arms and took three of us and [beat us] badly until we all collapsed. My blood come out from my mouth, nose ears and eyes. They handcuff[ed] each of us and put us in one small room and arrange[d] to send [us] near the border guard of Burma. Then they put us [in] the car and drove [in the] middle of the night. … [T]hey stopped for… whiskey. When they [were] in the restaurant, one of us, manage[d] to unlock all [three], and we [ran] into [a nearby] river. Me and Kune Shwe Thaik escaped by diving into water and [swam] across the river to other side … [to] hide in the near forest. It [was] the River Kwai.”

Having escaped from prison and fled from the Thai authorities attempting to send them back over to the Burma, Tint applied to Canada for political asylum, and arrived in Toronto on March 15, 1995.

Refuge in Canada

Tint was drawn to Canada because it was a democratic country — something that, by that point in his life, he had come to value through grave experience.

The adjustment to life in Canada as a refugee was not easy. Language barriers, harsh weather, and difficulty finding employment were just some of the barriers he during his transition.

After the move, many people found it difficult to understand his suffering and relate to his experience. Some discouraged him from ever becoming involved in politics again, regardless of where he was living. He did however, find support in a few people who did understand that the circumstances were beyond his control — especially those with knowledge of the devastating war back in his home country.

Yet, even in the face of perpetual challenges, Tint never lost his hopeful spirit. He said that he eventually came to learn that “…here in Canada, if you try, try hard, and work hard, you will succeed through all barriers.”

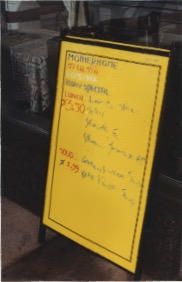

Just two years after arriving in Canada, Tint became the CEO, founder, and management head of Motherhome Inc., a Toronto based Burmese restaurant chain, which operated from 1997 to 2012. Tint had been working as a kitchen helper at Lisa Shamai Cuisiniere after arriving in 1995, but desperately wanted to continue his education as a way to secure stable employment, and ensure he could provide assistance to his family who had been detained in Myanmar.

Tint was unable to establish direct contact with his family, but through a friend, he managed to send money to them for food, clothing, and basic medicine. After a year as a kitchen helper, he became supervisor of the sandwich department. A year later, he bought a small coffee shop for $10,000 on Front Street West near the Rogers Centre.

Eventually, Tint managed to sell the coffee shop for more than what he initially paid, and upgrade to a bigger restaurant space in the same building. In 2005 he opened a second Motherhome location in Don Mills, and a third location in 2010 on Bloor Street West.

In 2012, however, Tint decided to leave his restaurant enterprise behind in search of something more. For him, education was the most important thing he needed if he was going to help rebuild his country.

So, in 2013 he commenced the Transitional Year Programme at the University of Toronto.

Tint is now pursuing a double major in English and contemporary Asian studies. For Tint, “English language is the most important to me and our country, for what our counterparts are saying, asking and meaning…Hence, to listen effectively, to speak effectively and to write effectively, I chose [to study english].” As for contemporary Asian studies, Tint “…love[s] to learn systematically about our regions to build a better Burma.”

As Tint contemplates the future for Burma he says, “I believe that… democracy… is the most important [thing for Burma right now] because it can bring peace and justice [to] stop the civil wars [so] that our generation can go to school, work, and live [safely].”

Putting his support behind recently elected Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy party, Tint hopes that Burma will soon become a place where people can freely choose their own government, and have a military that serves and protects its people — rather than one that rules over them with an iron fist. Since coming to Canada in 1995, Tint has been banned from returning to Myanmar. As he continues his study of the country from Toronto, his chief hope is for a change that will allow him to return to see his mother again, in his home country. For now, he is waiting and observing.

MOTHER

A poem by Htay Tint

Mother…

We have many brothers and sisters…

We all are surviving

and

growing up,

because we all had been fed with colostrum which make from you blood with benevolent.

We all had been slept by singing of your song, which you sang for us to sleep at sleeping time.

Mother…

We have many siblings, who always together even when we are in danger, disaster or difficult time.

We have many brothers

and

sisters who always take a place by the side of someone and we have many siblings who never be a bystander, and who ignore others.

Mother…

We are not disappointed when you are being failing or not being succeeding in your goals.

Because we all are your sons who have ability to through way of the mundane world, which in gain and loss, fame and dishonour, praise and blame, happiness and suffering.

Because we all understood that failing or succeeding is never be forever

and

it can be change in no time.

Mother…

We are all blooming in your garden as colourful flowers,

such as white,

red,

blue

and

green colour.

As we all come from east,

west,

south

and

north.

As we all go to different directions to north

east

or

south west.

As we all do middle or nowhere.

But we all, each go along with believe that what we believed.

We all had been taught by you to distinguish good and bad.

At one day,

Unexpected day,

At the day which we all, your sons and daughters expected day,

The gate of mother’s garden was being broken,

The garden of mother was destroyed,

We all had been brutalized at our school, home and motherland.

Mother…

We all had run to a place that they can’t reached,

We all had lived a place that they can’t attacked without defend them

Mother…

Although the world will disappear,

it never disappear from our heart that what they did it to the innocence people and us,

We will never forget and forgive,

We all are being known that we must sacrifice now for future,

We all do need nothing

except your love

that loving forever to you sons and daughters,

your motherland and the world.

Do not give up mother,

Do not give up your hope,

Do not giving up on your sons and daughters too,

Because we all are yours,

and yours only and ones.

Because we all have you as only and one.

Because, we will fight till we can choose…

And we will choose you to govern us, mother.

Dedicated to all mothers who lost their sons or daughters, or both, in 8/8/88. To all mothers who let their sons or daughters run away from danger and never reunion until now. To Daw Aung San Suu Kyi who fought for the people of her motherland. To my only, lonely and lovely mother who I left since 1988.