I’ve always thought certain types of writing should be private. Reflections in journals, letters to friends, notes passed in class — they’re handwritten, personal, and thus seem inherently confidential. It is unsurprising, then, that each of my diaries has “do not read” scrawled angrily inside the cover.

Naturally, I was intrigued when I heard about Jane Alice Keachie and Marsha McLeod, who are deliberately putting personal stories at the centre of public attention.

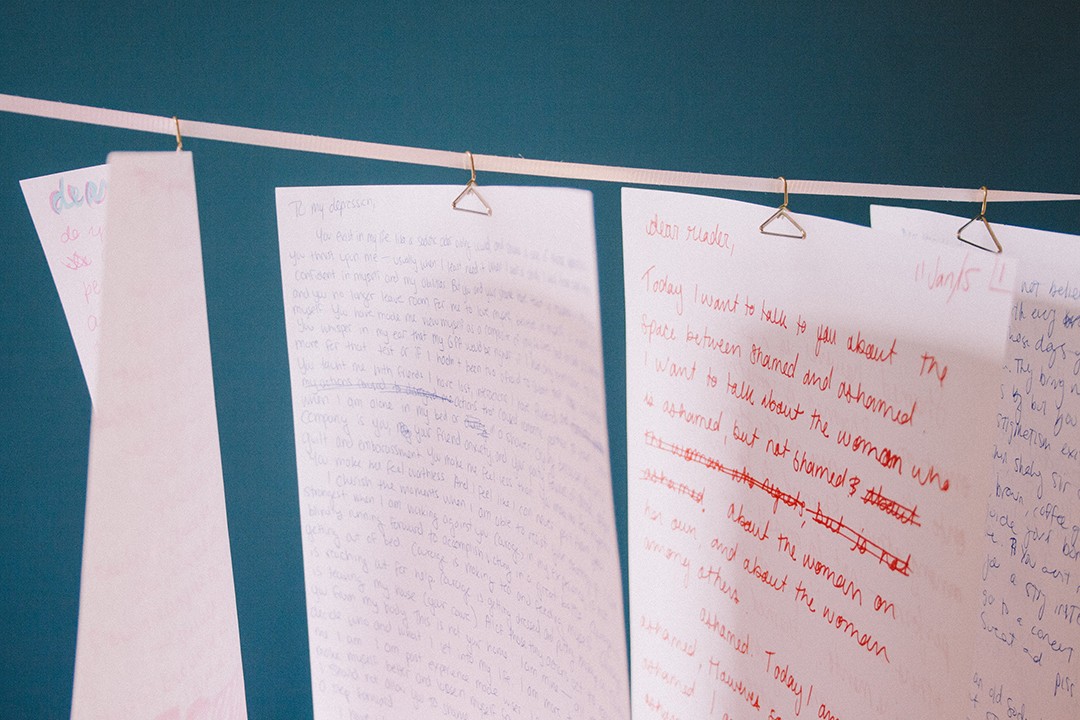

After realizing that the University of Toronto is sorely lacking in explicitly feminist publications and spaces, Keachie and MacLeod decided to create a feminist writing society, named HERE, in the fall of last year. At monthly meetings, contributors handwrite letters in response to a general prompt, with some choosing to read their work aloud. At the end of each session, Keachie and McLeod collect the letters, and later scan and upload them onto HERE’s website.

THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL

Even the quickest scan of HERE’s online archives reveals the intimacy of contributor’s stories, which recount experiences with body image, mental health, harassment, and, of course, sex.

To be entirely honest, I felt quite uncomfortable reading most of the passages. Not necessarily because of the nature of the topics, but rather because I could find myself reflected in certain elements of each story. It’s chilling to read a stranger’s particular account of navigating puberty and the shame that comes with it, only to realize I went through almost exactly the same experience.

“Once you start to interrogate your own life, you realize there’s a lot of fucked up shit that you thought was normal,” Keachie says, adding, “Once you start talking to someone else about it, you’re like, ‘There’s a bigger problem here.’”

Indeed, personal stories provide a visceral, accessible avenue to explore the seemingly abstract and broad issues of feminism and sexism. What’s more, the emphasis on the individual is a direct resistance against academic constraints on expression.

At such a large institution like U of T, students can end up feeling insecure, as though they’re just a number.

“We’re always taught to be objective, and take ourselves out. How am I supposed to pretend I’m not there?” McLeod asks exasperatedly. “This is about putting ourselves back into writing.”

A UNIQUE STYLE

HERE emphasizes the individual not only through their content, but also through their preferred form of expression. Handwriting effectively captures a writer’s personality, which could be lost in a standardized typeface. Since each type of handwriting is distinct, it forces readers to slow down and engage with the text.

Handwriting also makes editing a lot harder to do. While unedited work can be considered sloppy in the world of academia, Keachie and McLeod assured me that it encourages more meaningful and honest responses.

“People end up saying things they’ve never told anyone before,” Keachie explains, adding, “You start questioning, why have you been censoring yourself? Why don’t we talk about this?”

Letter writing was another deliberate stylistic choice for the group. Historically, letters have been a subversive form of communication for feminists. HERE recognizes itself as building upon this tradition. Letters aren’t articles or essays, yet they remain very direct and purposeful.

“I’m calling you out, I’m writing to you: an institution, a thing, myself,” McLeod says. “It has a point, because it’s to someone, and implicates something.”

I didn’t fully appreciate these sentiments until I actually tried writing a letter myself. Though it was outside of the group’s monthly meeting, I still felt the rush of confession through directing my letter to the HERE community. There’s also something immensely satisfying about seeing your own handwriting take up space.

GROUP VALIDATION

Perhaps most interesting is how HERE provides a space to have your voice heard, literally. The intonation, pauses, volume, and speed of reading out loud give stories personality which would otherwise be lost if simply read in someone’s head. Reading aloud also allows contributors more control over their work, and is an empowering practice.

Especially in the context of feminism, reading aloud amplifies feminist voices in a way that is desperately needed. It rejects the sexist caricatures of women as simply narcissistic or shallow for talking about themselves and is an antidote to the constant silencing of women who speak out about oppression.

“I think girls can often be made to feel silly when talking about feminism,” says Kendall Andison, a fourth-year contributor. “Sometimes it’s difficult to trust that what you have to say on the subject is of value.”

Consequently, reading out loud to attentive, like-minded listeners is a way of instilling a sense of ownership and pride in personal experiences. In fact, every contributor I spoke to expressed almost identical feelings of validation. Even the simple act of mailing my letter to HERE prompted similar, albeit diluted, excitement that my story was worthy of being published and read.

CREATING SAFE SPACES

Emphasizing personal experiences has the potential to promote greater inclusivity because all stories are appreciated. This is particularly significant for feminism, which has long been monopolized by white, heterosexual women. In fact, Manaal Ismacil, a third-year contributor, had a high school teacher once tell her that feminism was simply “a white woman’s approach to how white men treated them.”

As a queer black woman, Ismacil discussed how this rhetoric made her feel excluded for a long time. Such stories prompted Keachie and McLeod to specify in their constitution that HERE is safe space for everyone.

“We really emphasized from the get-go: if you have felt that feminism doesn’t include you, we want to be the kind of feminism that includes you,” explains Keachie.

Their dedication to inclusivity has been successful. All feedback thus far praises HERE for establishing a positive and nonjudgmental environment. There is little doubt that HERE will continue living up to their namesake: boldly taking up physical and intellectual space, declaring a feminist presence on campus.

Correction (February 26, 2015): A previous version of this article referred to “women’s voices.” This has been changed to “feminist voices” to reflect the broader inclusivity of HERE.