It’s no revelation that print media is dying. Rather, it’s the subject of most newsroom conversations, and should you forget about the Canadian media’s slow demise — if only briefly — any young journalist would be eager to remind you of it two or three times. Our media landscape, to say nothing of the one down south, has all but abandoned the physical copy of a newspaper in exchange for investments in digital output.

This has been played out through a number of painful cost-cutting methods conducted by major news outlets across the country over the last few years. In January 2016, the Toronto Star closed its printing plant in Vaughan, and it outsourced its print production to potentially increase focus on digital media. In September 2016, Rogers Media announced it would cut Maclean’s magazine from a weekly edition to a monthly edition. Earlier in 2013, The Globe and Mail cut its print edition in Newfoundland and Labrador and then, in November 2017, it extended this rollback to New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Globe consolidated its Arts section with the News section, mixed Business with Sports, and narrowed the lengths of its pages.

Circulation among all major media outlets has dropped. Even we at The Varsity dropped our weekly circulation from 20,000 to 18,000 copies in 2017.

Here, the Charles Dickens quote no longer applies — it’s definitely not the best of times, and it’s probably the worst of times.

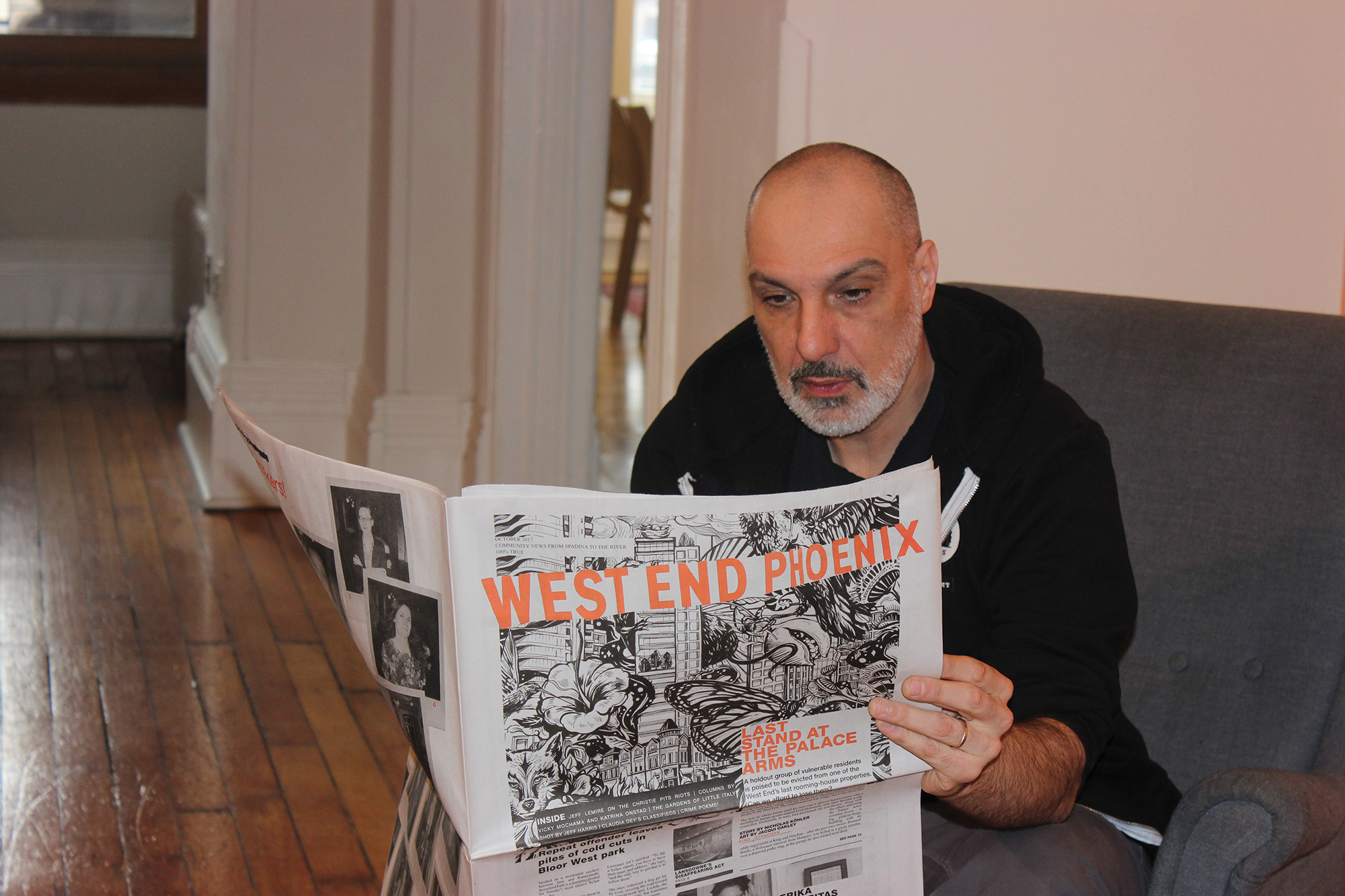

Dave Bidini though — pointedly not a journalist and yet the founder of a recently established local paper — isn’t having the worst of times. In fact, he’s having fun. The guitarist for the disbanded Rheostatics and a bohemian of the downtown core is now the founder of The West End Phoenix, a local monthly newspaper.

You probably haven’t heard of it, and there’s a reason for that: the West End doesn’t exist online. Its business model is antithetical to that of practically any paper in its vicinity. It’s print-only, ad-free, and cannot be found on newsstands but rather by home subscription. In place of articles, its website reads, “Thou shalt not PDF.”

The newly founded paper is not necessarily built to last — the website itself is headed with the quote, “You’re crazy, but good luck” — so it’s unsurprising, then, that when I meet with Bidini in the paper’s office, a bedroom-turned-workplace in the centenarian Gladstone Hotel on the outskirts of Parkdale, he’s knowingly tentative about the paper’s future.

“Honestly, we don’t even know if it’s going to work,” he tells me. “We have certain targets we want to meet — in terms of our subscription, in terms of our funding — [and] we may make it, it may be fantastic, [but] maybe we won’t. But we want to try.”

The paper is Bidini’s brainchild — an idea that came to mind after a visit to Yellowknife in 2015. The city’s local paper, the Yellowknifer, is akin to the purity of media prior to the digital revolution. It prints twice a week, and it is sold on the streets by kids with part-time jobs. It bears minimal online presence, existing only under the name of its parent company, Northern News Service.

When Bidini returned to Toronto from the north, he noticed an unfortunate contrast in the local papers here. “I remember one day The Villager appeared on my porch, and it was huge. But once you open it up, you realize it’s all… wrapped in flyers. All of the editorials have been gouged out — they were all bought by Metroland [Media].”

That’s when he decided to start a paper of his own. “We’re in this catchment in the west end, this amazing place in this amazing city — who’s telling the stories? I thought the opportunity existed to start a community paper that will be telling the stories of people who live here rather than it being a glorified coupon wrap,” he said.

The paper is funded primarily by subscriptions and patron supporters. Neither are cheap — a yearly subscription starts at $56.50, and the base patron donation is $200 — but it has roped in some interested buyers nonetheless. The paper has roughly 1,800 subscribers in the west end of Toronto and approximately 450 subscribers sprinkled across the rest of Canada and the world.

Bidini himself is in a unique position to take such a risk. Prior to his stint in journalism, he was known primarily as the guitarist for Candian indie rock band The Rheostatics. Bidini has since become a staple of the Canadian arts scene — a figure in the same circle as the late Gord Downie, Margaret Atwood, and other notable figures.

This status helped when forming the West End. “I was calling in every fucking favour of people I met in music [and] people I met in publishing,” says Bidini, which is why the list of major patrons on the newspaper’s second page reads like the starting lineup of Canada’s arts scene all-star team. Margaret Atwood, Yann Martel, Serena Ryder, Bruce McDonald, and George Stroumboulopoulos are but few of the names listed as “major” and “founding” patrons. The paper also received starting donations from TD Bank, Blundstone Canada, and Lake Ontario Waterkeeper, among others.

So why the aversion to publishing online? “Part of it is romance; part of it is nostalgia for sure,” explains Bidini. “Somebody contacted us the other day and said, ‘I’m looking for the name of the writer who did the story on tunnels for you guys,’ and my wife was like, ‘Isn’t that cool? That they had to write to us rather than find [these] names on the internet?’

Bidini dismisses the notion of the West End being anti-digital, but the obscurity of the product is certainly pointed. In some ways, the paper appears to counteract the rapid change that its geographic surroundings are experiencing. Parkdale, whose previously undesirable market value helped facilitate an influx of artists over the past two decades, is undergoing the familiar process of gentrification.

Implicitly, if not explicitly, the West End — in all its ad-free purity — appears to want to preserve the culture that some may fear is dissipating. As a paper that, for the most part, only locals know about, it lends itself to the preservation of a neighbourhood once unexposed to big business and overpriced condos. It’s not NIMBYism, but the process has stoked a collective need to preserve the old.

“By supporting the paper, you’re supporting the poet and the graphic designer, and the illustrator that lives on your street,” pitches Bidini. If the neighbourhood becomes unaffordable for the artist class, then the poets, graphic designers, and illustrators leave. And when they go, so does the heart of the neighbourhood. It becomes, as Bidini puts it, “less freaky.”

So is the project sustainable? “We’ll see,” says Bidini. “It’s an experiment. And I’d be an idiot to say it’s not a ‘can’t miss’ project.” In a media landscape that’s looking more and more like a battlefield, the success of a leisurely local is nowhere near guaranteed. But for a community trying to preserve a neighbourhood, perhaps there’s a demand.